Lactation Curve Series

Terragen’s Lactation Curve Series helps dairy farmers recognise some of the critical moments leading into – and after – a lactating cow gives birth. Some key areas in this series detail how farmers can aim to maintain a high standard of and to minimise negative impacts on their herd’s health and productivity and lets farmers stay ahead of the curve,

PART ONE – UNDERSTANDING THE CURVE AND BODY CONDITION SCORE

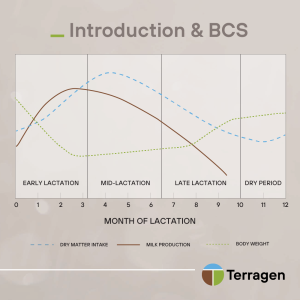

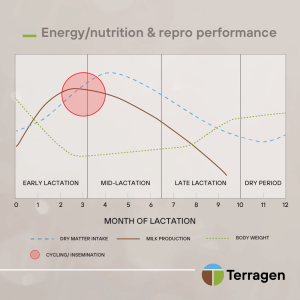

The lactation curve can be broken into four main stages: early lactation, mid lactation, late lactation and the dry period. The cow has different requirements and stressors in each stage. Managing these stressors has a significant impact on a cow’s productivity throughout its lactation, as well as its ability to get back in calf.

A transitional cow is in the period whereby she transitions from a dry cow into a lactating cow. This period generally includes the three weeks before and three weeks after calving. The transitional period is usually the most challenging period for a cow, so managing this period is critical to setting a cow up for a successful lactation. Deficiencies here (nutritional and non-nutritional) can have a detrimental impact not only on milk yield, but also health and fertility outcomes.

Body condition score (BCS) is a useful tool in assessing the fat and muscle of a cow in specific locations on her body; it is considered one of the top indicators of reproductive success in dairy cows. BCS removes size and weight considerations and when done skilfully, gives a standardised measure of a cow’s reserves. Using BCS well can give a good indication of how nutritional management is tracking on farm and subsequently help set targets specific to stages of the lactation curve. BCS can help draw conclusions on previous nutrition and estimated reproductive performance. Farmers can use BCS to get early indications on the performance of a cow’s diet, then make more informed decisions on whether diet alteration is required.

In Australia, BCS is usually measured on a scale of 1-8 (with 1 being emaciated and eight being morbidly obese). Cows with a BCS between 3-6 are generally identified as healthy. Some producers use external consultants to provide herd BCS data as they use this for the basis for nutritional alterations, especially during key points of lactation.

If you are worried about the condition of your cows or are interested in gaining more information, information from industry bodies can prove more than useful, while we suggest contacting your local large animal vet or experienced consultant.

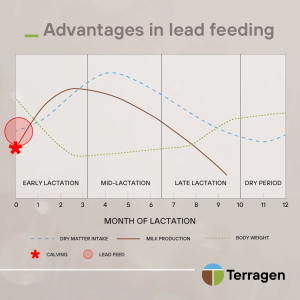

PART TWO – LEAD FEEDING

Lead feeding offers greater nutritional control in the period leading up to calving. When executed well, dairy farmers can use lead feeding to optimise production, health and fertility outcomes.

Lead feeding should aim to:

1. Increase dry matter intake (DMI) gradually and control energy to optimise body condition score (BCS) and meet upcoming higher nutritional and energy demands, preparing the rumen for increased intake post-calving. Cows should not be ‘over conditioned’ coming into the transitional period. The aim is to ensure cows are ready to milk on day one in the dairy and can cope with the increased energy demands of lactation. Managing DMI ensures the rumen and gastrointestinal system are primed for optimal intake and feed conversion efficiency in the weeks prior to calving.

2. Reduce the risk of metabolic diseases (such as milk fever, grass tetany or ketosis) and other disease or disruption associated with the pre-parturient and postpartum periods.

3. Support high-quality colostrum and greater milk production, which in turn maximises productivity and profitability.

Poorly adapted cows a have higher risk of disease, suffer greater impacts of energy deficit in early lactation, have reduced milk yields and the birthweight of their calves can be impacted.

Lead feed diets can be manipulated to achieve health and productivity outcomes in cows through:

1. Addition of necessary macrominerals (either in direct form or as anionic salts) to mitigate risk of metabolic diseases, particularly milk fever and microminerals to assist in immune function.

2. Feeding the right amount of concentrate before calving to condition the rumen while encouraging DMI. A cow should be gradually conditioned, so she is ready to increase DMI after calving. She should not be adapting to a completely new diet.

3. Including adequate fibre in ration, introducing any grain gradually and utilising rumen modifiers if necessary. This will minimise disruption to rumen function, most commonly sub-acute or acute ruminal acidosis.

4. Ensuring quality feed which is dense in energy and protein post calving to meet the increased demands of lactation.

5. Supplementing lead feed with a probiotic such as our MYLO® may help prepare your cows’ rumens by supporting digestion efficiencies, establishing optimal microbiota prior to the stress of calving and milking and reducing pathogen stress.

Advice specific to your herd should be sought from a trusted nutritionist, consultant or veterinarian.

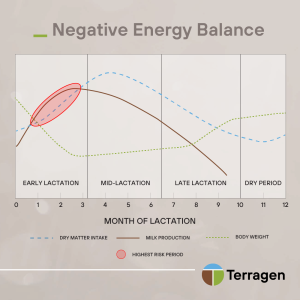

PART THREE – NEGATIVE ENERGY BALANCE (NEB)

NEB describes the physiological state in which a cow has an increased energy demand that cannot be met by her feed intake, therefore entering an energy deficit state. This usually coincides with early lactation when milk production demands rapidly increase. Most cows experience a degree of NEB as a normal physiological response to this demand, however adequate management can ensure duration and severity are minimised.

NEB is a key factor leading to health, productivity and subsequent profitability outcomes of an individual cow. Prolonged or extreme states of NEB can lead to health challenges including metabolic diseases, reduced milk yield, undesirable reductions in body condition and poor fertility outcomes. The first two weeks after calving are usually the highest risk of NEB and the period associated with greatest likelihood of disease.

Cows combat negative energy balance by utilising fat stores for energy – a process called lipid mobilisation. This process turns adipose tissue (fat stores) into readily available energy for the cow, in the form of non-esterified fatty acids (NEFA). Farmers who carefully manage this process will aim to minimise the severity and duration of negative impacts of lipid mobilisation. Prolonged or extreme periods of lipid mobilisation can lead to serious diseases such as ketosis, fatty liver and pregnancy toxaemia.

With the right nutritional support, cows can cope with and recover from NEB and as their milk yield starts to naturally decline after peak lactation, they are able to regain any lost body condition. Energy requirements fluctuate throughout lactation, but as a general rule, a cow’s demand is highest in early lactation, as the cow is building up her Dry Matter Intake (DMI) capacity. During this same period, a productive cow is expected to return to oestrus ready for joining. In mid and later gestation, good management means surplus energy becomes available to recover condition and allow healthy foetal growth.

Body Condition Score (BCS) helps indicate how cows respond to NEB. A significant drop in BCS tends to occur post calving but starts to stabilise 3-6 weeks into lactation. As a cow’s DMI increases, she should begin to regain body condition.

Recent results from Terragen’s Big Cow Project, conducted with The University of Queensland in Harrisville, 2023, found cows fed MYLO® in this period lost less weight than a control group, maintained a better body condition and recovered sooner than control cows. Blood glucose was found to be higher in cows whose diet was supplemented with MYLO®, indicating the potential for greater energy supply.

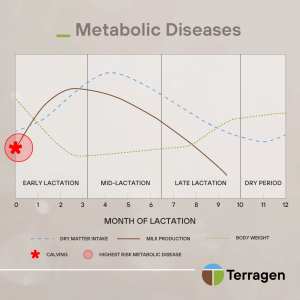

PART FOUR – METABOLIC DISEASES AND COW HEALTH MANAGEMENT

As touched on earlier in this series, lead feeding and careful management of a transitional cow to minimise Negative Energy Balance (NEB) can also play a vital role in preventing and managing metabolic disease. During this period of lactation, it is estimated that around 80% of disease occurs.

Key metabolic diseases may include:

– Milk fever (hypocalcemia or low blood calcium)

– Grass Tetany (hypomagnesemia or low magnesium) – Low Phosphorus (hypophosphatemia)

– Ketosis (low blood glucose and lipid metabolism resulting in ketone production)

– Pregnancy Toxaemia (severe lipid metabolism causing toxic build up of ketones impacting the brain)

– Combinations of the above (as these often go hand in hand)

Farmers should manage nutrition to optimise the rumen’s productivity, promote calcium metabolism and uptake, ensure energy and nutrient availability, and maintain immune health.

Key steps include:

– Minimise deficiencies: this is especially important in relation to feeding your cows macro minerals including calcium, magnesium and phosphorus. Leading up to calving, these minerals have significant roles to play to ensure high-quality colostrum, greater milk production, a smooth calving and a swift recovery.

– Reduce ruminal disruption: avoid any dietary changes or significant stressors that can lead to further appetite suppression or sub-optimal rumen conditions. The NEB period can be a time when farmers change their cows’ diet; encouraging increased intake is common. Consider avoiding acidosis or sub-acute ruminal acidosis by ensuring any diet change occurs gradually (particularly if increasing grains or concentrates) and incorporating appropriate fibre.

– Reduce the duration and severity of lipid mobilisation associated with NEB by managing body condition score in the later stages of lactation and nutrition through the transitional period (such as with lead feeding).

Cows require a significant amount of energy to maintain their immune system and fight disease. Providing ample energy and protein intake combined with athe balanced inclusion of select trace minerals and vitamins all helps.

The use of probiotics, such as MYLO®, can improve digestion efficiencies and promote optimal rumen function while also outcompeting pathogens, helping improve health outcomes for cows in this challenging period.

PART FIVE – VOLATILE FATTY ACIDS AND GLUCOSE

If the transitional period is challenging for a cow – particularly those that are highly productive – her fertility can be significantly compromised.

VFAs and glucose (available sugar) are vital for the health and reproductive performance of the dairy cow.

VFAs are the end products of microbial fermentation. They are the predominant energy source for the cow and therefore imperative to every function.

Key VFAs include acetic acid, propionic acid and butyric acid. Diet and rumen health are the main factors which impact VFA production. VFAs can make a large impact on reproductive health and performance of the dairy cow.

VFAs can influence reproduction in the following ways:

– They impact ovulation – VFAs, especially propionic acid, are thought to have a significant impact on follicular development and ovulation.

– They impact reproductive hormones – VFAs can influence the production and availability of reproductive hormones including GnRH (gonadotrophin- releasing hormone) and LH (luteinising hormone). These hormones are crucial for ovulation (synthetic forms are utilised in common artificial insemination programs)

– They have been attributed to uterine health. Buytric acid has been found to play a role in maintaining uterine pH. Uterine health is essential for successful implantation and maintenance of pregnancy.

Meanwhile, glucose, as a primary source of energy in cows, is imperative for reproductive performance. Diet, body condition and metabolic status can impact glucose levels. Extensive periods of low glucose (brought upon by Negative Energy Balance) can delay ovulation or the onset of oestrus, thus reducing fertility.

Glucose also helps a cow’s immune cell function and her overall health. When a cow is sick, a significant proportion of energy is directed to the immune system to restore her health. Therefore, low levels of glucose over time can also result in a vulnerable immune system, making the cow more susceptible to disease and lower reproductive performance. Glucose is a precursor of lactose, the key sugar in milk. To maintain optimal milk production, a consistent level of glucose needs to be maintained.

A cow’s Body Condition Score (BCS) is a key indicator when it comes to the impacts of glucose levels and NEB. Optimal glucose metabolism aids in maintaining ideal BCS as glucose directly impacts fat synthesis and mobilisation. Optimal BCS is often correlated with reproductive success.

Recent results from Terragen’s Big Cow Project, conducted with The University of Queensland, Harrisville, 2023, found cows whose feed was supplemented with MYLO® maintained better body condition after calving and had higher glucose levels than control cows. It was also found that cows fed MYLO® presented for artificial insemination 9.6 days earlier than control groups indicating improved reproductive performance.